Understanding Action Research: Characteristics and Practical Applications for PhD Scholars in Education

Understanding Action Research: Characteristics and Practical Applications for PhD Scholars in Education

- Home

- Academy

- PhD Research Methodology

- Characteristics and Practical Applications for PhD Scholars in Education

Understanding Action Research:

Recent Post

Introduction

For PhD researchers in education, action research represents a strong, empowering approach to bridging theory and practice in their own educational context. It allows researcher-practitioners to critically analyse their own educational context, take stock of the complexities of education, and design and evaluate context-appropriate responses. In terms of practical action research and participatory action research, they differ in scale and emphasis; however, they have a set of defining characteristics that shape both how they are developed and applied. Understanding and acknowledging these characteristics will help doctoral candidates design meaningful, ethically authentic, and rigorous reflective studies.

Key Characteristics of Action Research

- A practical focus

- The researcher’s own professional practice

- Collaboration

- A dynamic, cyclical process

- A plan of action

- Sharing research and results

1. A Practical Focus

Action research is intended to focus on authentic, immediate concerns within a school setting. For doctoral researchers, this means focusing on those issues that permit immediate improvement in teaching, learning, or how a whole institution is functioning. As Stringer (2007) notes, action research relies on practical problems that lead to immediate improvement within the educational community.

Example: A PhD candidate employed as a principal of a school can research the impact of peer-mentoring programs on retaining new teachers. Or, a university lecturer can explore the influence of using reflective e-portfolios on student engagement in hybrid courses. In both examples, the research is producing direct evidence to improve education, not just developing knowledge for the sake of developing knowledge.

Common Challenges & Tips:

Challenge: Due to the organizational or funding nature, more obstacles may be experienced.

Tip: Consider framing the project in reference to what the organization or funding agency is measuring for their change or improvement plans. Context is key to administrative support and audience relevance!

2. The Researcher’s Own Practice

A prominent feature of action research is its reflexivity, in which the researcher examines their own professional practice. The educator–researcher becomes both the subject and the subject of inquiry, continually reflecting upon and improving their practice. This dual identification of acting and observing, separates action research from other approaches that seek to understand data while the researcher is not a participant in the research.

Action researchers purposefully study and try out their own practice as a teacher, leader, or administrator to examine the impact on practice and refine it based on data. Action research has been described as a “spiral of self-reflection” (Kemmis, 1994, p.46), where each cycle brings better understanding and improved practices.

Example:

A teacher–researcher studying differentiated instruction might try out new strategies and techniques over two semesters – observing any shifts or changes in student performance – and then modify techniques based on reflection and data as necessary.

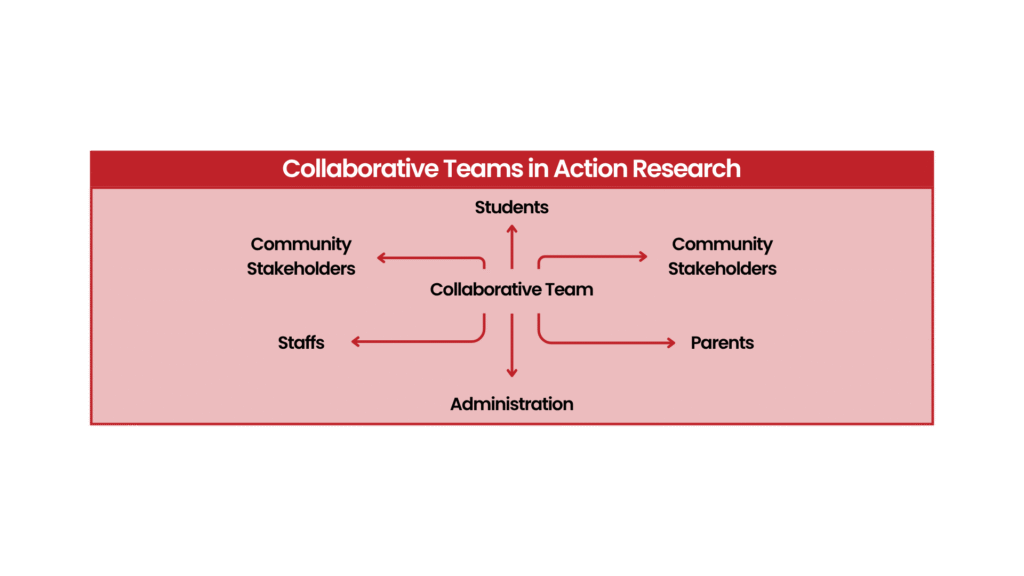

3. Collaboration

Collaboration is at the heart of action research. Schmuck (2009) points out that effective action research frequently requires coparticipants, such as other teachers, administrators, or outside partnerships, such as university researchers or community organisations. Collaboration increases the reliability and significance of the findings and increases the likelihood of shared authority and collective responsibility for change.

However, as Stringer (2007) warns, collaboration does not mean that you have co-opted practitioners. External collaborators must negotiate their roles and design a collaborative process in partnership with practitioners to ensure that practitioners remain the key decision-makers throughout the inquiry process. A quality collaboration involves building positive relationships, inclusive and transparent modes of communication, and sharing outcomes and responsibilities.

Example:

A PhD student studying digital literacy may work with other colleagues to collaboratively design and evaluate new lesson plans that employ ICT. Peers provide feedback to adjust the intervention to contextually appropriate issues.

Challenge + Stratergy:

The balance between professional relationships and research can be nuanced when colleagues are also research participants. Being explicit about research participant roles, consent forms, and data use of will help sustain trust and ethical practice.

4. A Dynamic, Cyclical Process

Action research uses a cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection which promotes flexibility and iterative improvement. The next cycle is based on the prior one, accommodating the researcher’s changing understanding and situations (Stringer, 2007).

Example:

- Cycle 1, after implementing a peer-assessment activity in a class.

- Cycle 2: After reflecting on student feedback, incorporate new assessment criteria in the rubric.

- Cycle 3: After trialling the new, amended model and evaluating its impact.

This cyclical nature gives action research its dynamic and flexible characteristics—an ideal found in action research doctoral projects, where data is emerging to inform the next cycle.

PhD Relevance:

Documenting each cycle with transparency (problem → plan → action → reflection) enhances methodological rigour and renders your dissertation process-oriented and evidence-based.

5. A Plan of Action

A clear plan of action is essential. The action plan can take several forms—initiate a pilot program, test several different temporal strategies, or create a change process that spans higher education. As Stringer (2007) states, the action plan is a formalisation of reflection through systematic, collaborative practice.

Example:

If you discovered that students decreased their participation, your plan would need to include using gamified learning resources, collecting engagement data, and making modifications based on student feedback.

6. Sharing Research

While the primary intention of traditional, academic research is journal publication, the priority of action research is dissemination to practitioners and local stakeholders. Action researchers are concerned that their results are shared with those who can quickly grapple with the findings; in the case of educational action researchers, this would be with teachers, school administrators, and community members (Hughes, 1999).

Dissemination locally does not eliminate the possibility of an academic publication but enhances the possibility of one later. Mills (2011) points out that the ability to disseminate action research online, in practitioner journals, blogs, and discussion forums, significantly increases dissemination, thereby providing rapid shareability and creating opportunities for feedback.

Example:

A doctoral researcher might disseminate their findings to a board of education, conduct a professional development workshop, and then write an academic article distilling findings for a wider audience.

Why This is Important for Doctoral Researchers:

Local dissemination can enhance the impact of research because it demonstrates knowledge translation, which passes through doctoral assessment and some boards of review.

Putting It All Together: Why Action Research Benefits Doctoral Scholars

Action research offers PhD students an authentic setting for academic inquiry and professional development. The inquiry allows researchers to:

- Engage educational or institutional problematics in situ.

- Develop their practice as critical reflective practitioners and change agents.

- Develop and enact evidence-informed interventions appropriate to their contexts.

- Engage with educational reform and innovation beyond the walls of academia.

Action research challenges us to balance reflection and rigour, collaboration and independence, action and documentation. Properly designed, action research changes both the researcher and the context of the research.

Practical Advice for PhD Researchers

- Begin with a manageable scope and build on the cycles incrementally.

- Keep detailed notes and reflections during your process.

- Regularly engage with and discuss your findings with your supervisors and colleagues.

- Ground your methodology in an established action research framework (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988; Stringer, 2007).

- Be ethical and transparent in your work when involving participants.

“Action research is not merely about changing practice—it is about transforming understanding.” — Adapted from Kemmis (1994)

References

- Kemmis, S. (1994). Action research. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., pp. 42–49) Oxford and New York: Pergamon and Elsevier Science. https://epaa.asu.edu/index.php/epaa/article/viewFile/678/800

- Schmuck, R. A. (Ed.). (2009). Practical action research: A collection of articles (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239770434_Action_research_literature_2008-2010_Themes_and_trends

- Stringer, E. T. (2007). Action research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Subject guide to books in print. (1957–). New York: R. R. Bowker.

- Hughes, L. (1999). Action research and practical inquiry: How can I meet the needs of the high-ability student within my regular educational classroom? Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 22, 282–297.

- Mills, G. E. (2011). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher (with MyEducationLab). (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.